JUNE 30, 2016

JUNE 30, 2016

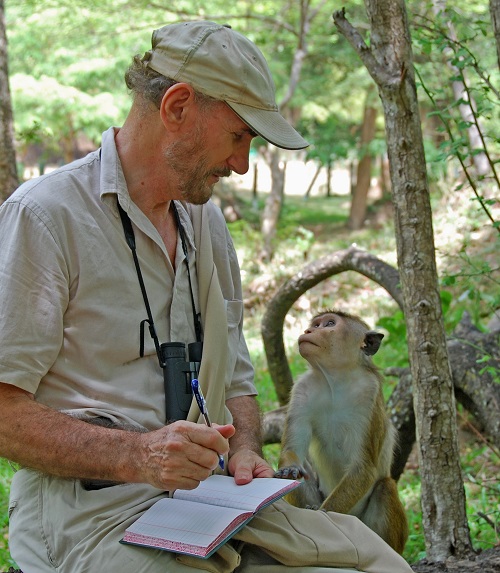

For nearly 50 years, Smithsonian Conservation Biology Institute primatologist Wolfgang Dittus has studied and lived among the toque macaques in Sri Lanka. In our Q & A, he reveals how family relationships, intelligent behavioral strategies and a healthy environment are key to this species’ survival.

Want science delivered straight to your inbox? Sign up for the e-newsletter here.

OUR AUDIENCE MAY HAVE NEVER HEARD YOUR NAME, BUT YOU AND JANE GOODALL ARE NECK IN NECK FOR THE LONGEST RUNNING PRIMATE STUDY IN THE WORLD. WHAT PRIMATES DO

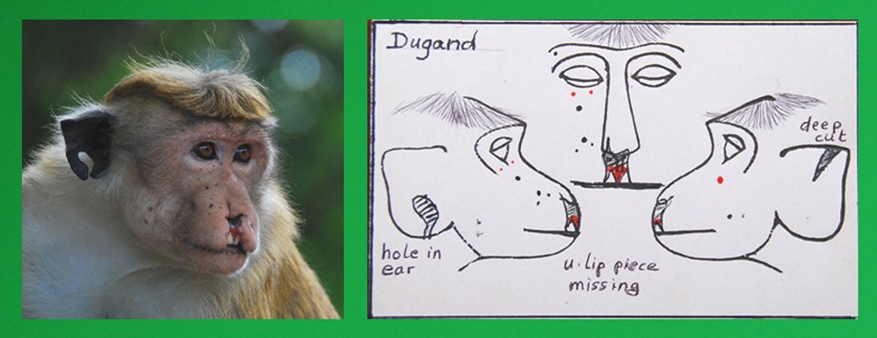

For more than 48 years, I have been researching toque macaques at our study site in Polonnaruwa, Sri Lanka. Over the years, we’ve studied more than 4,000 macaques. We want to identify key behaviors and measure how they contribute to macaques’ ability to survive and reproduce in a changing environment. One important method we use to keep track of who is who, is making ID cards for individual macaques that include their identifying characteristics.

One of my goals as a scientist is to teach people how wonderful these monkeys are. People will only be willing to help conserve species that they love. They will only love these species if they understand them, and they will only understand these species if scientists (myself included) are telling the animals’ stories.

ID card for adult male toque macaque, Dugand

WHAT WAS YOUR MOST MEMORABLE EXPERIENCE IN THE FIELD?

Juvenile toque macaques are very inquisitive and much more likely to take risks than the adults. I was just standing and observing them when one juvenile approached and touched me! When I first started the study, it took me a long time to habituate these monkeys to me being there. Once they’re used to a person, they don’t run away, but they don’t necessarily approach, either. I let my beard grow for quite some time, and when I finally did shave the monkeys ran away from me! It took them a day or two to get used to me again.

WHAT HAVE THE MACAQUES TAUGHT YOU ABOUT PRIMATE BEHAVIOR?

It might surprise people that family is the most important social bond or relationship that a macaque can have in its society. They take care of each other, and the females tend to form sisterhoods. Sisters help one another, and grandmothers and aunts are also there to assist.

Animals form social groups of closely related families that are, essentially, coalitions to defend their turf against neighboring families of similar structure. So, females have female bonded sisterhoods that are defense coalitions against other such groups.

But, these relationships are a double-sided coin. The macaques will form social alliances and cliques within the larger group. This can lead to very strong jealousies within families. There is a social hierarchy that determines how the monkeys divide the group’s food and other resources among themselves.

The mother is the highest ranking, followed by the youngest daughter, then the second youngest daughter, and so on. The reason why the youngest daughter—not the oldest—ranks second is because she is smaller and less experienced than her older siblings. The mother will come to the defense of the youngest sibling every time.

Interestingly enough, the young ones learn this quickly and will take advantage of this and act as though an older sibling has wronged them in some way. Then, mom swoops in to discipline the older sister! So, as long as mom is around, the younger sister dominates the older. Of course, when mom isn’t around, the older sister will try to get back at the younger sister.

HOW DOES THEIR WEIGHT AFFECT THEIR ABILITY TO SURVIVE?

Macaques have long survived in a variable environment, competing with other monkeys and a whole host of critters. They really depend upon their brains and intelligence to make a living. They’re omnivorous, and fruiting trees are dispersed throughout the jungle. Often, they have to travel distances to find them. They’ll also eat insects and spend about 20 percent of their day foraging for them!

Most arboreal mammals tend to be small, which helps them reach flimsy terminal branches where fruit and young leaves grow. Our research showed that in arboreal monkeys and macaques, fat isn’t just randomly distributed in their bodies; instead, it’s distributed in such a way that gives the proper balance in mass to the body as these arboreal primates leap and climb around, balance, and maintain their locomotion in these unstable tree platforms.

It turns out that toque macaques, like many other mammals, have less than 5 percent body fat. Any fat gained is distributed in such a way that it is away from their joints (where it could interfere with locomotion) and helps to stabilize their center of gravity.

When babies are born, they are skinny little things that have about 1 percent body fat. That’s because mom can’t afford to carry around a large baby during pregnancy; it would make her unstable when she has to swing from branch to branch. It wasn’t until the transition from arboreal primates to terrestrial ones that it was physiologically and anatomically possible for females to have lots excess fat that they can then give to babies through their milk. Fat is critical for developing large, intelligent brains such as are found in the human lineage.

WHY ARE SOME NATIONAL PARKS PROBLEMATIC FOR PRIMATES?

The biggest threat to conservation efforts around the world is loss of habitat. Often, national parks are designated on land that is not agriculturally productive. However, if the land is not good for agriculture, it is unlikely to support the plant growth that vegetarians need to eat!

Some national parks have grasslands, so grazers like elephants and deer tend to thrive. Macaques, on the other hand, are dependent on a perennial supply of water from streams or permanent ponds. Unfortunately, those water sources are only found in gallery forests, which represent less than one percent of national parks.

In Sri Lanka, the lowland wet forest and rainforests are a productive habitat, but that’s also where much of the human settlement has occurred. Most of the rainforests have been cultivated for human development and timber. It’s a constant battle at a political-economic level to set aside productive protected land.